INTRODUCTION - PERCEPTION OF THE CITY

A metropolis of diversity, vibrancy and segregation, Mumbai has both sculpted become a chaotic urban landscape with socially bipolar characteristics. As the fourth most populous conurbation in the world with over 12 million people, (Census data 2011) Mumbai is an overcrowded, yet capable modern city. Perceived through its own systems and mainstream representation, Mumbai offers the the opportunity to study complex layers of social, domestic and public spheres. The dialect between political, territorial and, social identities is frequently conflicting, abrupt, parallel, even overlapping. This can be seen through the self-built, turbulent slum territory juxtaposed against the modern skyline and formal housing; a backdrop of investment and development. With this comes the idea of the public, private and perceived social spheres, and the key roles of housing and gender within. As one of 10 countries to recognise ‘the third gender’, male, female and transgender identity shape the city and define social use of space in the home and public realm.

Formerly Bombay, Mumbai was renamed in 1995 after the goddess Mumbadevi of the Kolis people,indigenous fisher folk, who consider her as their mother (aii meaning mother in Marathi) (The British Library Board, 2019).

A city of two worlds, segregation is prevalent in such abrupt extremes when considering the housing typologies throughout the urban footprint. Slums are defined as “a contiguous settlement where the inhabitants are characterized as having inadequate housing and basic services.” (UN-Habitat, 2010). These self-built developments are home to 41.3% of the Mumbaikar population compared to the Indian national average of 9% (World Population Review, 2019).

Such immediate transition between these territories is visible across Mumbai with formal housing and slum developments existing almost conterminously, both approaching the constructed boundary as if in a standoff. To understand this stark division in Mumbai living, it is essential to draw upon geographical and historical factors resulting in or challenging the facilitation of housing.

EXPLAINING MUMBAI'S HOUSING CRISIS

Mumbai, geographically, is on a peninsula. The room for urban sprawl is limited and constrained, وthus the growing population is directed further from the area of formal housing in a linear fashion rather than other cities which can spread more radially.

Challenging topogrpahy towards the north of the city further reduces the amount of developable land. Other large cities have more negotiable terrain while Mumbai is pressured into a smaller inhabitable area.

FSI (Floor Space Index), governed by the municipal body, dictate the density restriction in a city (Bertraud, 2004). As Mumbai’s FSI is so low, the city has spread outward, reaching beyond the extremities of improvement schemes nearer the CBD. This low restraint has lead to an array of vernacular housing typologies across Mumbai ranging from deprived makeshift dewllings to formal housing.

BRINGING HOUSING AND WOMEN INTO THE CITY

Mumbai’s mass housing emerged following the textile industry under the East India Trading Company, which ultimately led to “one of the most interesting developments of the modern era” for women (Robb, 2002, p238). Mass immigration of workers to the city provoked the Bombay Development Dictoriate, formed in 1920 to build over 200 four or five storey chawls for workers in the textile precinct in central Mumbai (Dwivedi, 2001. pp199). Defined as a “large building divided into many separate tenements” chawls offered “cheap, basic accommodation to labourers”. (Oxford Dictionary)

Architect Sir Claud Bately describes these chawls as “cheerless, architect less, gardenless” (Dwivedi S. 2001, p210). Despite external appearances, the functionality and convenience of these chawls are a practical way of providing social housing; close proximity to suburban railway stations and housing 20-25 workers in a 10x12ft single room tenement (made possible by the variation in working hours in the mill throughout the 24 hour period). The chawls made efficient use of space and offered affordable housing close to work. Semi-public spaces, corridors, were wider in comparison to the contemporary equivalent self-build and offered a playground and community hall. By the turn of the 20th century, these chawls began to have an effect on women in Indian society. It became important to move the family closer to work, bringing the site of production and reproduction closer. This was a step towards changing the role of women as part of a movement of equality in the public sphere, more out of financial necessity than active gender reconditioning. Nevertheless, this urbanisation and housing transition allowed women to exploit their potential socially, politically and economically (Koppikar, 2017).

Upon the industry’s collapse, the southern seafront territories of Cuffe Parade,Worli and Marine Drive were occupied by the rich mill owners. The housing typology consistent of “large apartments in the art deco buildings, with long balconies over-looking the sea fronts” reflecting the contemporary rich (Adarkar, 2003, 4531). Meanwhile migrant labour began to reclaim to marshy lands adopting a self- build lifestyle and grew to form todays slums. This visible divide of housing through Mumbai’s urban fabric can be superimposed on a less visible, but prevalent social division of gender. The south of the city is perceived as a “forbidden” area for slum dwellers and for women (Adarkar 2003 p 4531). Gender, therefore, can be seen on the city scale with housing to form an identity and perception of an individual socially, dictating the usable spatial territory in the public sphere.

SLUMS IN THE CITY

Today, labourers in Mumbai chose to live in similar sharing conditions to chawls, often with even smaller public spaces. For those looking to avoid the cumbersome commute across the city, workers opt to live in self-build slum dwellings to be close to work. For some it is not an option but either a condition from birth, or an unavoidable eventuality.

Dharavi is the shadow city within Mumbai. As the largest slum in India, the former fishing settlement now has an uncertain population with estimates ranging from 300,000 to 1 million residents in a 557 acre territory (Lewis, 2011). Dharavi is a self-built, self-supported housing development. With 15,000 single room factories, 5,000 businesses, schools and shops, it has a population density 10 times that of the city average. As one of the most popular and recent portrayals of life in Mumbai slums, Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire - while met with some reviews of ‘romancing the slum’ (Eggebrecht, 2015) - depicts Dharavi as a chaotic scene. It portrays a dense fabric of built form, tight, claustrophobic spatial qualities and a destitute atmosphere, and overcrowded homes and streets. A study by Guggenheim lab when regarding private spheres, describes how 26% of respondents feel they need privacy from neighbours, while 24% wanted privacy from family (Dasgupta, 2012, p10). Indian tradition mentions the importance of family, and seen as a female role in society. This research into privacy in slum areas suggests overcrowded is to such extremes that privacy is near non-existent.

Typically, these slum dwellings are a single 10 square meter room, housing 8 people. The crowded conditions give an average of 48 square feet per person, less than the minimum requirement for an American prison cell; drastically different from the provision of privacy from formal housing typologies. As such, inhabitants make efforts to increase the area of usable space, using limited space multifunctionally

USING GENDER TO EVALUATE SLUM HOUSING

Aarti Grover describes the construct of ‘gender’ as “socially-learned behaviour and the expectations from society”. Taking this approach on how people use domestic and public spheres, the self-defined idea of gender identity is constrained to the “expectations of women and men, in relation to their social role and duties” (Grover, 2015). While Grover argues this is a constructed phenomenon and societal perceptions of ‘the individual’ philosophically could consider a more self-determined nature, adopting this ideological method as a lens allows us to better distinguish the gender among housing and society in Indian culture.

Guggenheim, describing itself as ‘part urban think tank, part community centre, part public gathering space’ (Guggenheim, 2019), is a forward thinking project-based research lab in Mumbai, Berlin and New York. In the case of Mumbai, researcher Christine McLaren claims “women act, in some respects, as a sort of indicator species for the health of various city systems” (McLaren, 2013). Health statistics in slums in Maharashtra (province) 2006 provide an insight to the conditions in these settlements.

When interpreting these figures it must be addressed that the female gender is inherently characterised in the nature of Indian culture as “[belonging] in or near the dwelling” (Grover, 2015), and so will spend more time in the slum settlement. The correlation between the poor condition of slums and ill health of inhabitants are reflected when considering this gender-based occupancy of the city. In the domestic sphere, women are often tasked with obtaining, transporting, purifying and using water, requiring more privacy in sanitation and lavatory use. An Indian article states one Dharavi toilet can serve 1,440 slum dwellers (Sinha, 2006). Women are the gender associated with the need to speak to children privately and are “naturally the most vulnerable” in dangerous spaces (McLaren, 2013). While formed from cultural constructs and the social sphere, these gender roles reveal slum housing as an unfit means on living, further embedding the inferior position of women in Mumbai.

Through the lens of National Geographic photographer Jonas Bendiksen, we see the relationship of people and the dwelling. As men use the home as a refuge from an external societal role, the woman provides domesticity in the kitchen and between family, fulfiling her societal role within the home.

GENDERING THE HOME

The gender perception and delegation of the home can be seen as one of the most intrinsic elements in urban Indian culture. Just as class division may determine the situation of the home, wealth may determine the size. Social influence and personal taste may affect the presentation of the home. Yet gender remains a prevalent feature throughout.

Housing in Mumbai, and on a greater scale - the globe, tends to compartmentalise the dwelling based on gender. Studying an abstracted home in the Indian subcontinent, Leslie Wiesman, in Discrimination by Design, describes how these spatial structures are arranged. Taking this “territorial dichotomy” in a domestic sense, Wiesman describes “the home as a metaphor for society” (Wiesman, 1994, p86).

The dwelling is organised into two spatial relations; the upper rooms, exterior and east in are associated with ideas of “above” “male”, “heaven”, “worldly”, “sunrise” while the interior, lower levels and west are “below”, “female” “downward”, “behind”, “sunset”. (Wiesman, 1994, p12). In gendering the home, parallels can be drawn on the societal composition and perceptions of gender in the city, dictating female inferiority. In mentioning this hierarchy, the idea of the female at the centre of the home is forgotten. Referring to Wiesman’s critique, the hearth and ritual centre, while less outwardly presented to the public realm, is the foundation and basis of the dwelling. In some respects, this could be congenial to the role of women within the household and society.

The rise of the ‘nuclear family’ in the mid 20th century became central to urban domestic culture of the formal housing sector in Mumbai (Adarkar, 2003, p4532). New exclusive properties catalysed a change in the middle class image of modernity, with new gadgets such as the fridge as a staple of the home and, in turn, womens’ role in Indian cultural aspirations. In leaving the chawls, there became a demand for private housing to fit this western ideal.

The satirical Femme/Maison, Louise Bourgeois, 1947, depicts themes of the woman contained in a domestic role, her identity taken by her position in the home and nude vulnerability or weakness in society. With the ideal of the nuclear family in an exclusive dwelling, and the gendering of the home, this graphic depicts the social/domestic position women were confined to in the private sphere.

1960s plotted developments with floor size 204m2 per tenement and large balcony. p63 LEFT

1970s apartments with floor size 86m2 per tenement, smaller balcony and denser construction. p69 MIDDLE

1980s Public sector and employee housing with floor size 49m2 per tenement and loss of balcony. p75 RIGHT

The home, and women, are often seen in Mumbai to be as one; women lack identity without the home, and likewise the home could not exist without women. In viewing women as the ‘hearth’ in the home they are the foundation element without which the home would not exist. An alternative perspective on Wiesman’s gender critique of domestic space as a “metaphor” for society, this too is the case for women in all social spheres.

“If by strength is meant moral power, then woman is immeasurably man's superior” - (Mahatma Gandhi, 1930)

Gandhi regarded women as a force of regeneration, intuition and endurance. He believed women were exemplars of courage and self-sacrifice at the heart of the family. In Gandhi’s paradoxical philosophies, because of the woman’s dependency and perceived stature of social weakness, she is strong. As with Vienna’s gender mainstreaming as a feature of housing construction, progressive movements and individuals in Mumbai look to redefine the private and domestic spheres with equity.

TRANSGENDER IDENTITY, HOUSING AND COMMUNITY

Although India is one of the few countries to legally recognise the ‘third gender’, and have been acknowldged in ancient literature, Mumbai’s transgender community still face with social challenges and met with discrimination. Hijras (female transgenders), appear in the ancient Kama Sutra, Mahabharata and the Ramayana texts. They are celebrated in Mumbai society, yet are still one of the “most marginalised groups within the country” (Delliswararao, 2018 p12). Hijras are forced to look for housing more so than males or females as result of being disowned by a parent in fear of bringing ‘disgrace’ upon the family. As with the construct of gender in the public sphere, this perception reduces the third gender below men and women. A report of a hijra finalising a flat was upon viewing personal documents when the broker “told [her] they did not have a flat for [her]” (Rakesh 2018). Fellow tenants “would not be able to adjust or be comfortable around her” (Sarkar, 2018) in another instance. Landlords will use economic deterrents to discourage members of thecommunity finding a home, charging 50% higher rates (Laha 2015). While hijras seem to have few additional difficulties finding eployment compared to males and females (Shah, 2015 Black Sheep), there is no enacted law for specifically providing protection third gender property interests. As recent as January 19th 2019, 77 new homes have been provided in Raipur for transgenders, the first step in a potential new development in housing for the third gender.

WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE

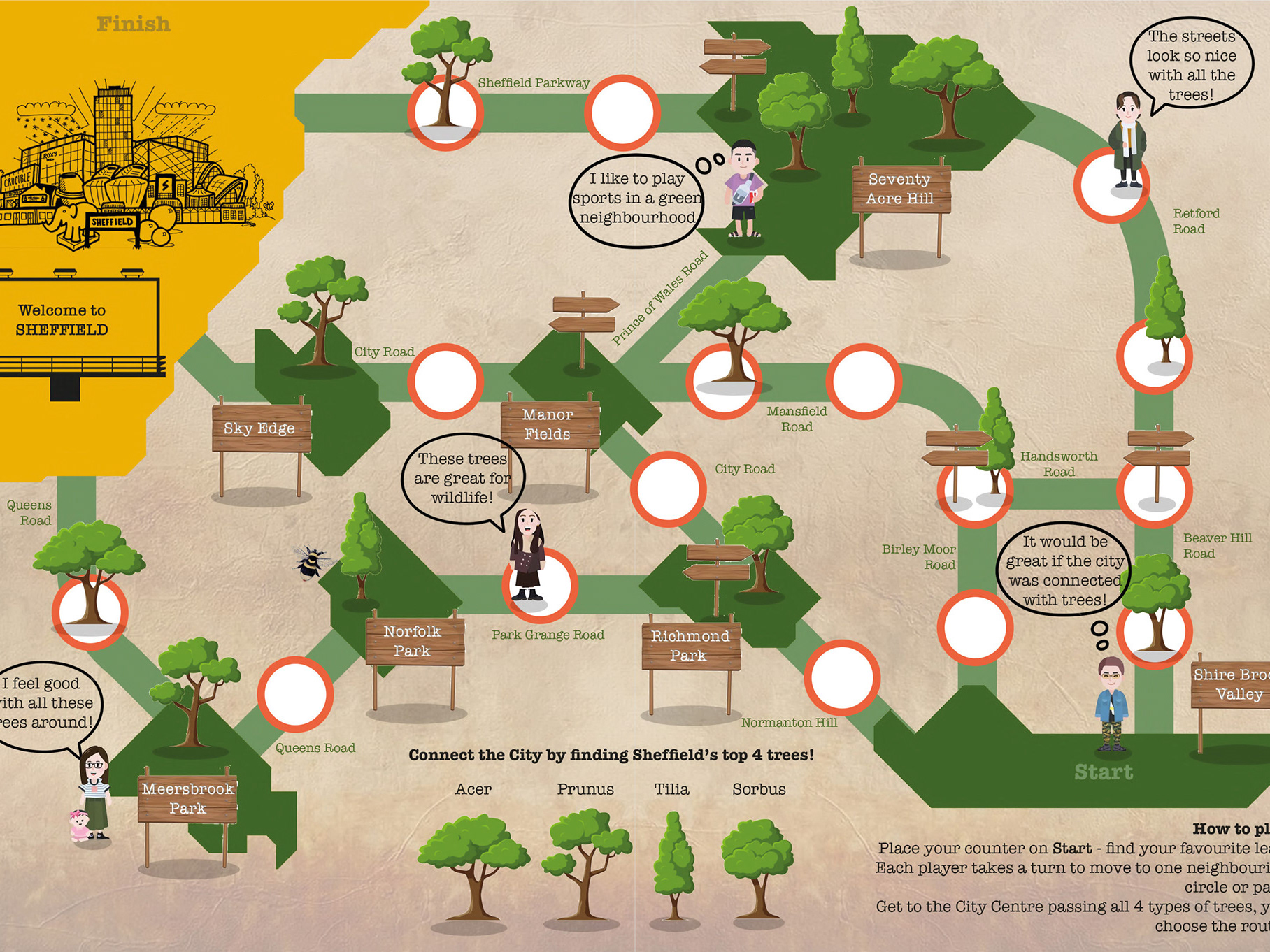

Housing is the base of the social community we call the urban world. Weisman describes “the streets as an extension of the domestic environment” (Weisman, 1994 p 67). In reference to the city, the same way we affect and influence our own private domain, together we can form a collective in the public sphere. To think of Mumbai is more to imagine a streetscape - how might women interact with the public sphere or be the subject thereof? The image below maps a streetcape in Dharavi by gender by observation of the users in the space. Bridging from the woman’s supposed ‘comfort’ zone in the home, the public sphere, or external environment remains true to Weismans interpretation; male dominated. Of 339 female respondents in Guggenheim’s investigation ‘Your Space, My Space, or Our Public Space?’ in Mumbai, only 23% of women felt public space was accessible, with 80% giving a gender related reason (safety, harassment, perception, men)

Ali K. (2017). Times Now News, ‘Among world’s most dense cities, Mumbai stands still at two’ available at <https:// www.timesnownews.com/india/article/where-world-most-dense-populated-cities-mumbai/61774 accessed 21 Jan 2019 Anon. (2009). Knoema ‘Reinventing Dharavi, 2009’ available at <https://knoema.com/awfdup/reinventing-dhara- vi-2009> accessed 22 Jan 2019

Anon. (2017). The Times of India ‘Mumbai: Centre labels 645 sq ft flat as affordable home’, available at <https://time-sofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/mumbai-centre-labels-645-sq-ft-flat-as-affordable-home/articleshow/58201234. cms> accessed 17 Jan 2019

Anon., (n.d.). The British Library Board ‘Bombay: History of a City’ available at <http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/ trading/bombay/history.html> accessed 14 Jan 2019

Census data. (2011).

Dasgupta, D. (2012). Guggenheim, ‘Your Place, My Place, or Our Public Space?: Privacy and Spaces in Mumbai’, available at <http://www.bmwguggenheimlab.org/where-is-the-lab/mumbai-lab/mumbai-lab-city-projects/priva- cy-and-spaces-in-mumbai>

Delliswararao K., Hangsing C. (2018). ‘Socio–Cultural Exclusion and Inclusion of Trans-genders in India’, Int.

J. Soc. Sc. Manage. Vol. 5, Issue-1: 10-17 available at <https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/IJSSM/article/down- load/18147/15566> accessed 16 Jan 2019

Dwivedi, S., Mehrotra, R. (2001). ‘Bombay: The cities within’. Eminence Designs Pvt. Ltd. p199-204

Eggebrecht P. (n.d). ‘Romancing the Slum: Conflict of Cinematic Style and Realism in “Slumdog Millionaire” by Paige Eggebrecht’available at <http://blogs.brandeis.edu/representingpoverty/featured-annotated-film-clips/romancing-the-

Grover A. (2015). Zingy Homes ‘Designing Urban Public Space’s Available at <https://www.zingyhomes.com/lat- est-trends/urban-public-space-design-gender-culture/> accessed 17 Jan 2019

Jose, Sunny and K. Navaneetham (2008) ‘A factsheet on women’s malnutrition in India’ Economic and Political Week- ly, 43(33): 61-7) p266

Kaiser, H. (2017). The Borgen Project, ‘How India is Serving the Growing Delhi Slum Population’ available at<https:// borgenproject.org/growing-delhi-slum-population/> accessed 20 Jan 2019

Koppikar S. (2017). Hindustan Times, ’Bombay’s freedom trail: Workers, strikes and a mutiny’ available at <https://www.hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/bombay-s-freedom-trail-workers-strikes-and-a-mutiny/story-OgwCe1vrm-HzrSTqkysbQ3O.html>

Kundu N., 2003 ‘UNDERSTANDING SLUMS: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements 2003 : The case of Kolkata, India’ available at <http://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu-projects/Global_Report/pdfs/Kolkata_bw.pdf> accessed 21 Jan 2019

Laha H. (2015). Hindustan Times, ‘Hunting for a home not easy for transgenders’ available at <https://www.hindu- stantimes.com/real-estate/hunting-for-a-home-not-easy-for-transgenders/story-eKnNNU4ZYdlbCkPt0ZCtRM.html> accessed 18 Jan 2019

Lewis C. (2011). Times of India, ‘Dharavi in Mumbai is no longer Asia’s largest slum’ available at <https://timesofin-dia.indiatimes.com/india/Dharavi-in-Mumbai-is-no-longer-Asias-largest-slum/articleshow/9119450.cms?from=mdr> accessed 16 Jan 2019

McLaren, C. 2013, ‘Women in the City: Examing Mumbai’s Gender Issues available at <’https://www.guggenheim.org/ blogs/lablog/women-in-the-city-examining-mumbais-gender-issues> accessed 17 Jan 2019

Metropolis World Association of the Major Metropolises (2011). ‘027 London (United Kingdom) Available at <https:// web.archive.org/web/20110427084411/http:/www.dgcl.interieur.gouv.fr/sections/a_votre_service/lu_pour_vous/ les_grandes_metropol/downloadFile/attachedFile/metropolislondres.pdf?nocache=1254397828.63> Accessed 20 Jan 2019.

Nambiar S. (2017). Culture Trip, ‘A Brief History Of Hijra, India’s Third Gender’ available at <https://theculturetrip.com/ asia/india/articles/a-brief-history-of-hijra-indias-third-gender/> accessed 15 Jan 2019

Parmar M. S. (2009). ‘A case study of slum redevelopment in Jaipur, India: Is neglecting women an option?”’ available at <http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTURBANDEVELOPMENT/Resources/336387-1272506514747/Parmar.pdf> accessed 19 Jan 2019

Ravi P. (2018). The Borgen Project, ‘10 Extremely Relevant Facts About Poverty in Bangalore’ <https://borgenproject. org/10-extremely-relevant-facts-about-poverty-in-bangalore/> accessed 21 Jan 2019

Sarkar G. (2018). Mid-day,‘Transgender woman unable to find home in Mumbai after brokers, flatmates reject her’ available at <https://www.mid-day.com/articles/transgender-woman-unable-to-find-home-in-mumbai-after-brokers-flat- mates-reject-her/19253178> accessed 18 Jan 2019

Shetty P., Gupte R., Patil R., Parikh A., Sabnis N., Menezes B. (2007). ‘Housing Typologies in Mumbai’, available at<https://critmumbai.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/house-types-in-mumbai-final.pdf> accessed 22 Jan 2019

Sinha K. (2006). The Times of India, ‘One toilet for 1,440 people at Dharavi’ available at <https://timesofindia.india-times.com/india/One-toilet-for-1440-people-at-Dharavi/articleshow/387002.cms> accessed 19 Jan 2019

Solomon R. (2012). BMW Guggenheim Lab, ‘Pop-Up Garden’ available at <http://www.bmwguggenheimlab.org/multi- media/media/187?library_id=1> accessed 15 Jan 2019

Statista (2019). ‘Population density of Singapore from 2005 to 2016 (in people per square kilometer)’ available at<https://www.statista.com/statistics/778525/singapore-population-density/> accessed 10 Jan 2019

Tabarrok A. (2015). George Mason University 2018 George Mason University 2018, ‘Rent Control in Mumbai’<https://www.mruniversity.com/courses/principles-economics-microeconomics/rent-control-mumbai-india> accessed 13 Jan 2019

The World Bank (2018). ‘Population living in slums (% of urban population)’ available at <https://data.worldbank.org/ indicator/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS?end=2014&start=1990&view=chart> accessed 21 Jan 2019

Times of India, ‘Mumbai: Centre labels 645 sq ft flat as affordable home’ available at

UN-Habitat (2010). ‘Chapter 1: Development Context and the Millennium Agenda. The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements 2003’ available at Khttps://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2003/07/GRHS_2003_ Chapter_01_Revised_2010.pdfL accessed 20 Jan 2019

Vienna Municipal Department 18 (MA 18) – Urban Development and Planning (2013). Wien Step 2025, ‘Gender Main- streaming in Urban Planning and Urban Development’ available at <https://www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/studien/ pdf/b008358.pdf> accessed 20 Jan 2019

Weisman L. K. (1994). ‘Discrimination by Design, A Feminist Critique of the Man-Made Environment’, p11-14, p72-86 World Population Review (2019). ‘India’, available at <http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/india-population/> accessed 19 Jan 2019

World Population Review (2019). ‘Mumbai’ available at <http://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/mumbai-popula

World Population Review (2019). ‘World’ available at <http://worldpopulationreview.com/continents/world-population/> accessed 19 Jan 2019

Young, S. (2017). The Independent, ‘England has the smallest home in Europe, new research says’ available at<https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/england-smallest-homes-in-europe-canada-largest-hong-kong-smallest- world-find-me-a-floor-a7597636.html> accessed 20 Jan 2019